One of the features the OS X Mail app offers is encrypted email. OS X Mail allows the user to send digitally signed or encrypted email to protect your electronic communications. I’ve written about digital certificates before. The idea is to use a special key — a digital certificate — to sign and encode your email so that only the intended recipient can read it. Encrypted email is a great way to send confidential information — passwords, social security numbers etc. — without worrying about who might intercept my email. An SSL email certificate ensures your mail cannot be read by anyone but the intended recipients. It also ensures your message was not modified during transmission and allow recipients to confirm your identity as the sender of the message1.

In this post, I will walk you through the steps to securing email in OS X. The steps to follow should allow you to encrypt your email communications in any mail application on OS X.

Getting a digital certificate

I use free email certificates issued by certificate authority StartSS but you can also get free certificates from Comodo or spend some money and get one from Symantec. The key is to make sure you get a certificate from a trusted source. Getting an email certificate requires you to fill out a form on the certificate authority web site with some basic information and then waiting for a confirmation email. Once you have received the email, follow the instructions to download and install your certificate. On Mac OS X that means downloading the certificate file and opening it in Keychain.

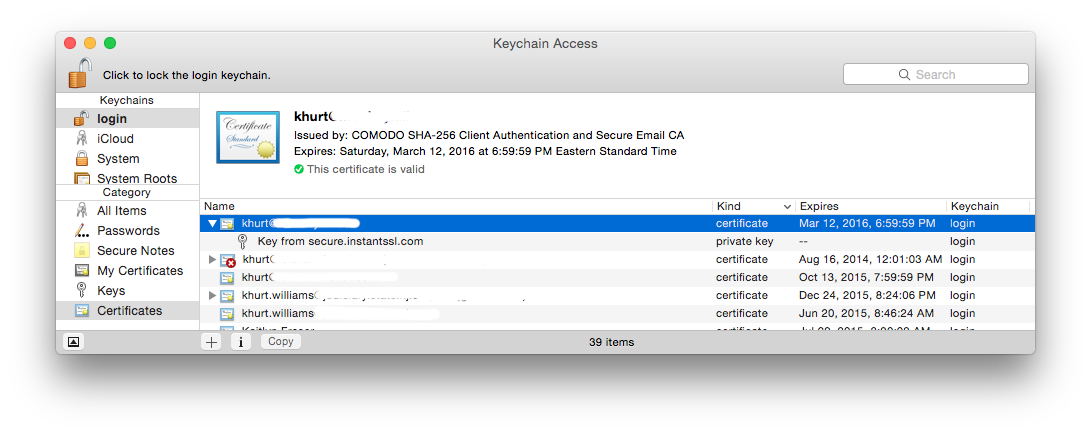

Keychain Access

Once you receive the confirmation email from the certificate authority, follow the instructions to download the certificate to your Mac.

On Mac OS X digital certificates are stored in OS X Keychain Access. The certificate file will have a file extension that indicates it contains certificates—such as .cer, .crt, .p12, or .p7c. Locate the certificate file and double-click to import into Keychain Access. Once you import your certificate, it should be listed in the My Certificates category in Keychain Access. If Keychain Access can’t import the certificate, try dragging the file onto the Keychain Access icon in the Finder. If that doesn’t work, contact the CA to ask if the certificate is expired or invalid.

Alternatively, you can launch Keychain Access (look in the Utilities folder inside the Applications folder) and type Shift-CMD-I to import the file. Once the certificate file has been imported I strongly recommend that you save your certificate to a safe place if you need to reload it later. I keep mine on an encrypted USB flash drive.

Open your certificate in Keychain Access and make sure its trust setting is “Use System Defaults” or “Always Trust.” Now you can use the certificate to send and receive signed and encrypted messages.

Using the certificate for encrypted email

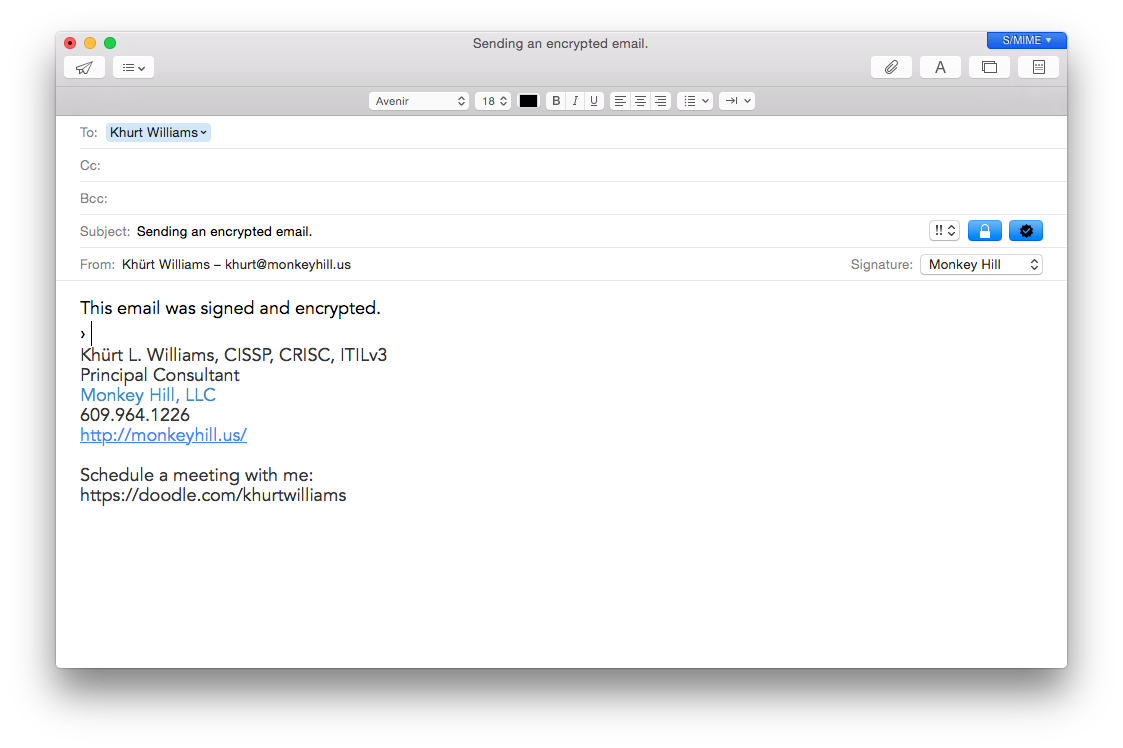

A signed message lets the recipients verify your identity as the sender; an encrypted message offers an even higher level of security. To send signed messages, you use your personal certificate from your keychain but to send encrypted messages, the recipient’s certificate must be in your keychain.

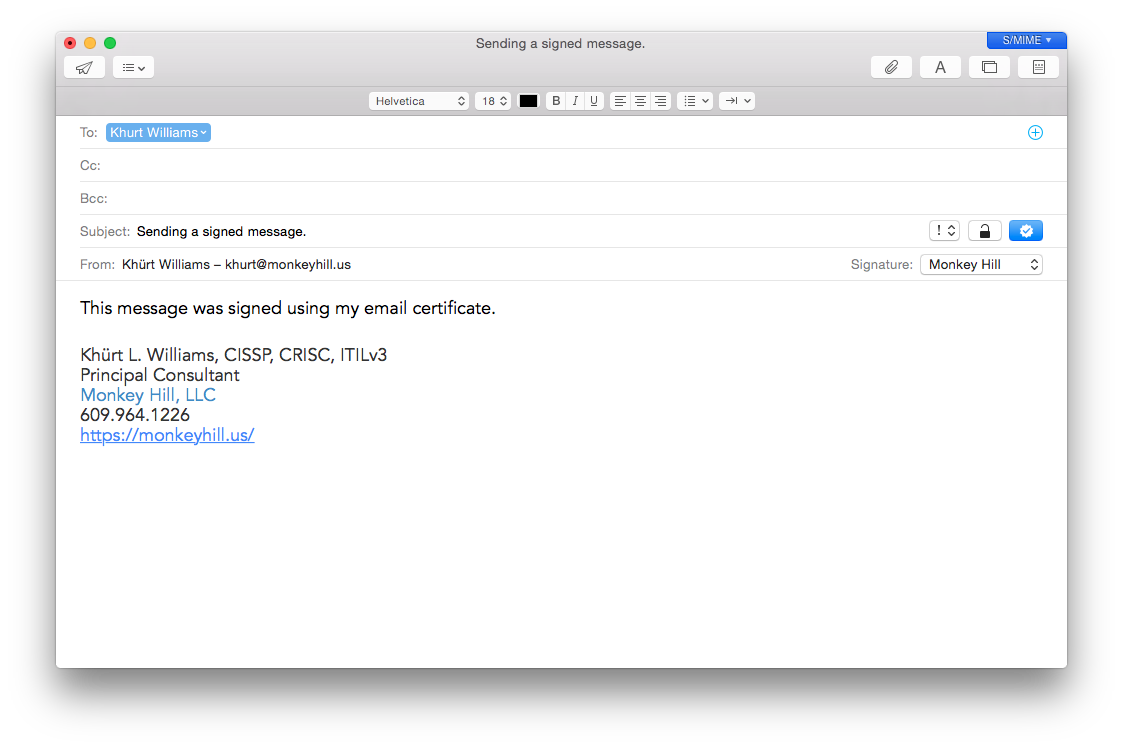

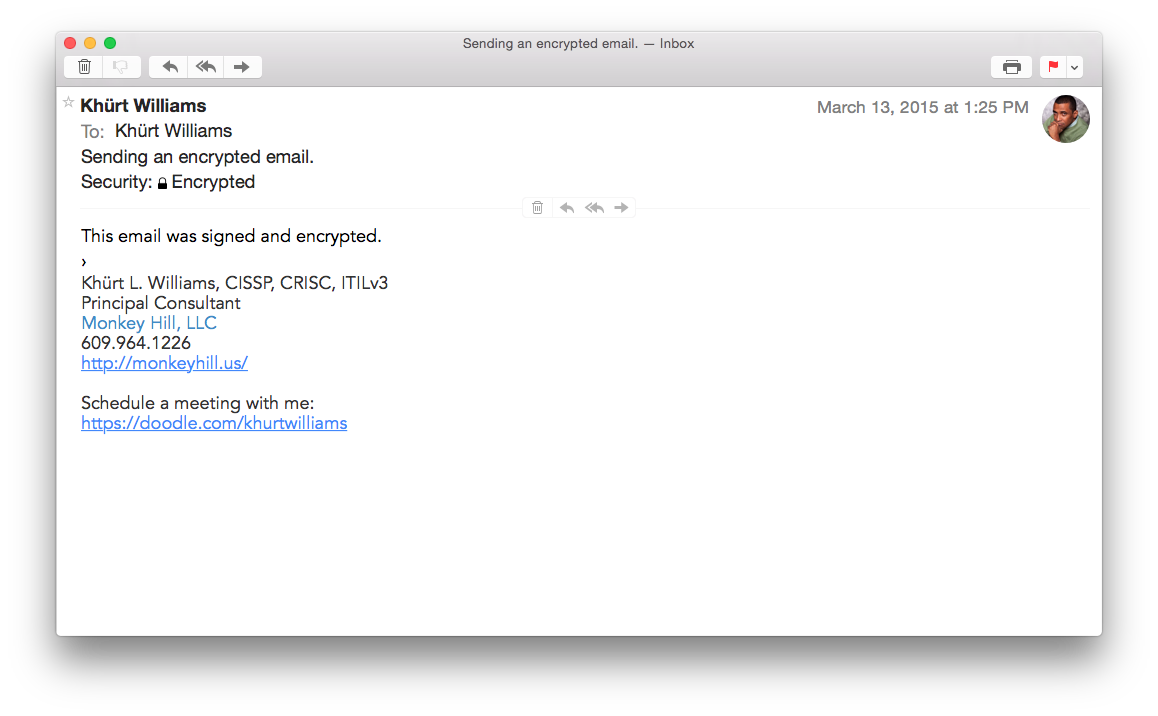

Open OS X Mail and create a new message. Choose the email account for which you have a personal email certificate in your keychain. OS X Mail includes a security field in the header area that indicates whether a message is signed or encrypted. A signed icon (containing a check mark) in the lower-right side of the message header indicates the message will be signed when you send it.

To send the message unsigned, click the Signed icon; an “x” replaces the check mark. An encrypt (closed lock) icon appears next to the signed icon if you have a personal certificate for every recipient in your keychain; the icon indicates the message will be encrypted when you send it.

If you don’t have a certificate for every recipient, you must cancel the message or send it unencrypted (click the Encrypt icon; an open lock icon replaces the closed lock icon).

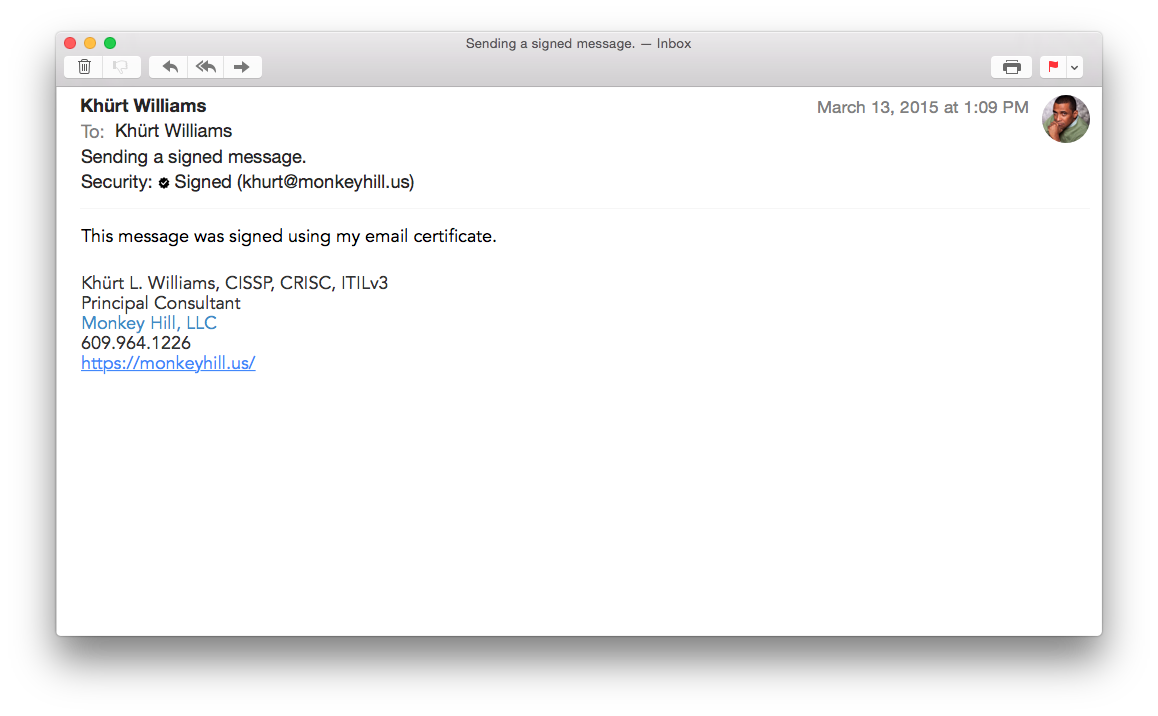

When you received a signed message, an icon (a check mark) appears in the header area of a signed message. To view the certificate details, click the icon.

If the message was altered after it was signed, OS X Mail displays a warning that it can’t verify the message signature. A lock icon appears in the header area of an encrypted message. If you have your private key in your keychain, the message is decrypted for viewing. Otherwise, Mail indicates it can’t decrypt the message.

To include encrypted messages when you search for messages in Mail, set the option in the General pane of Mail preferences. Although the message is stored encrypted, the option enables Mail to search individual words.

- I’m simplifying a lot here. Read my original article for more detail on digital certificates. ↩