Despite the promise of increased interactivity and web integration, the IndieWeb plugins have limited adoption, compatibility issues with WordPress themes, and social platform sharing. After removing all the IndieWeb plugins in 2020, over the last few years I found myself reinstating several and exploring new ones to enhance my WordPress website's IndieWeb capabilities. I re-installed almost all the IndieWeb plugins: IndieAuth, Webmention, Post Kinds, and Syndication Links. Although, it’s not a great-looking theme because I want full compatibility with the IndieWeb plugins I am using a Microformats 2-compliant child theme for Twenty Sixteen.

I hope my statements don't suggest a dislike for the IndieWeb community's efforts. I’ll borrow words from Daniel Goldsmith who wrote:

To begin, and before I get into anything else, I need to state this loudly and clearly: I like the Indieweb movement. I like the aspirational statements which underpin the movement. I like the people involved, I've interacted with more than a few of them and have found them to be, almost without exception, among the most earnest, polite and encouraging people I've ever met online.

I removed all the plugins except Webmention and Syndication Links. There are several reasons.

IndieAuth works by allowing me to use my website URL as the identity for authentication and authorization on websites that support it. Here's a simplified overview of how it operates:

- User Identification: When I want to log in to a website, I enter my website URL, `https://islandinthenet.com/`.

- Discovery of Authorization Endpoint: The website connects to my WordPress websites and looks for an

authorization endpoint. This endpoint is configured in the HTML or HTTP headers of my WordPress website. - Authentication Request: The website redirects me to their discovered authorisation endpoint with a request to authenticate.

- User Authorization: At the authorization endpoint, I prove ownership of my URL, usually by logging in to the service that hosts the endpoint.

- Redirection and Token Verification: After successful authentication, the authorization endpoint redirects me back to the original website with an authentication token.

- Confirmation: The original website verifies the token with the authorization endpoint to confirm my identity and then grants access.

But I rarely come across websites that use IndieAuth. The only website that I know supports IndieAuth is the IndieWeb Wiki.

Post Kinds is a concept within the IndieWeb community that categorises various types of content a person might want to publish on their website. These types, or "kinds," include articles, notes (similar to toots), photos, videos, replies, likes, reposts, and more. The Post Kinds WordPress Plugin adds support to the Classic Editor to implement this concept by enabling me to classify my website content into these different kinds.

But except for "replies" the Post Kinds plug-in isn’t useful to me and I rarely. Even when I’ve used the reply post kind feature I found that very few websites supported Webmention which is required to make use of many of the post kinds.

I don’t do microblogging on my website so I’ve never had use for the Simple Location plug-in.

Webmention and Syndication Links offer the most potential for engagement. Webmention is a simple, standardized protocol for my website to notify another when it links to it. For example, some post something on their website. I write a response on my website and include a link to their post. My website sends a Webmention to their site, informing their website of the link. Their site verifies the Webmention by checking my post to confirm it indeed links to their post. Once verified, their site can display my response as a comment, like, share, etc., depending on the context.

Syndication Links are a way to indicate that a piece of content published on my site is also available via a link on another site. For example, if I write a blog post on my website and also share it on Twitter, I can use a syndication link on my blog post to point to Twitter.

Webmention and Syndication Links work together to create a more interconnected and rich web of content. Let’s say someone publishes a post on their website and shares it on Twitter, adding a syndication link on their original post pointing to the tweet. I see the tweet, write a response on my website, and my website sends a webmention to the original post. The originating website receives the webmention, verifies it, and then shows my response as a comment. The syndication link to the tweet is also displayed.

I think it’s very cool. Yet, its effectiveness is limited. Most social platforms I use, barring micro.blog, don't support "rel=me" linking and most blogs do not support webmention.

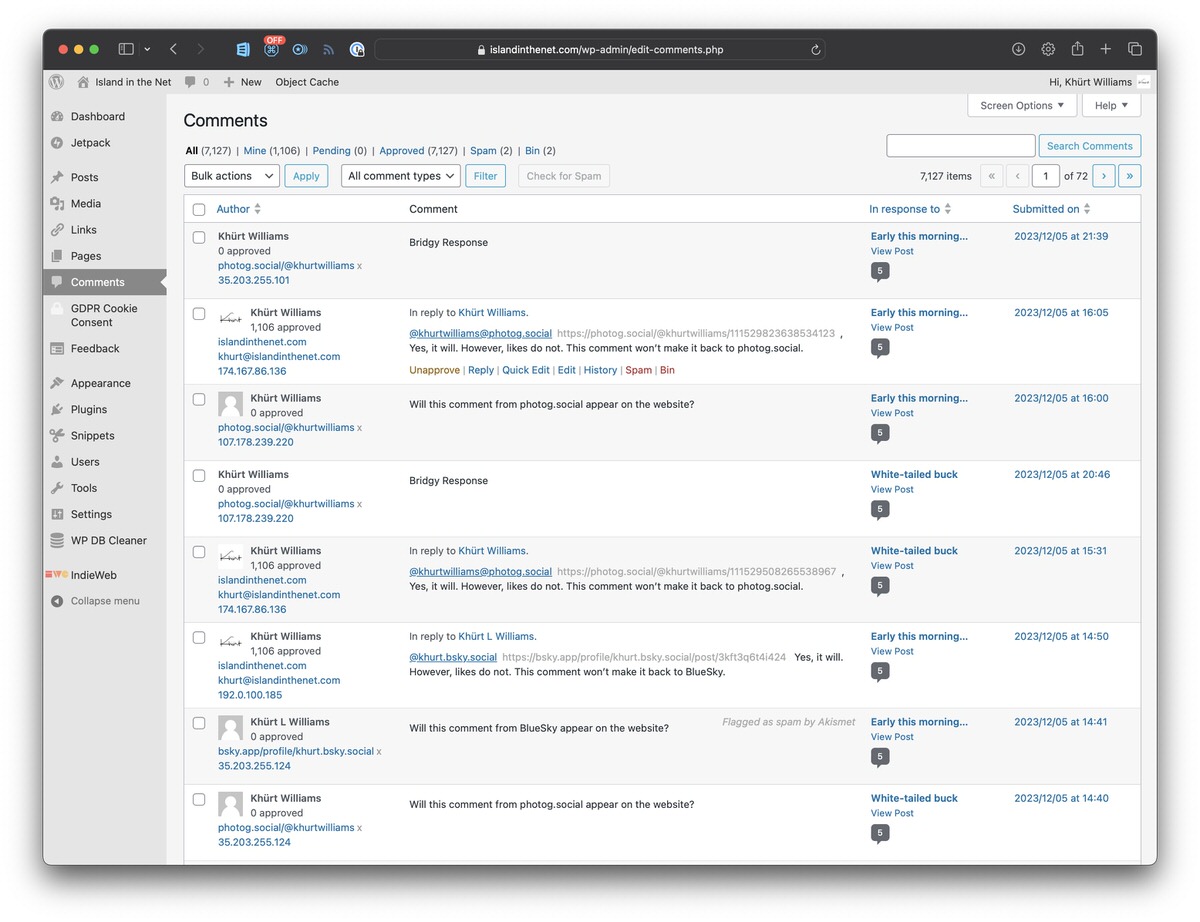

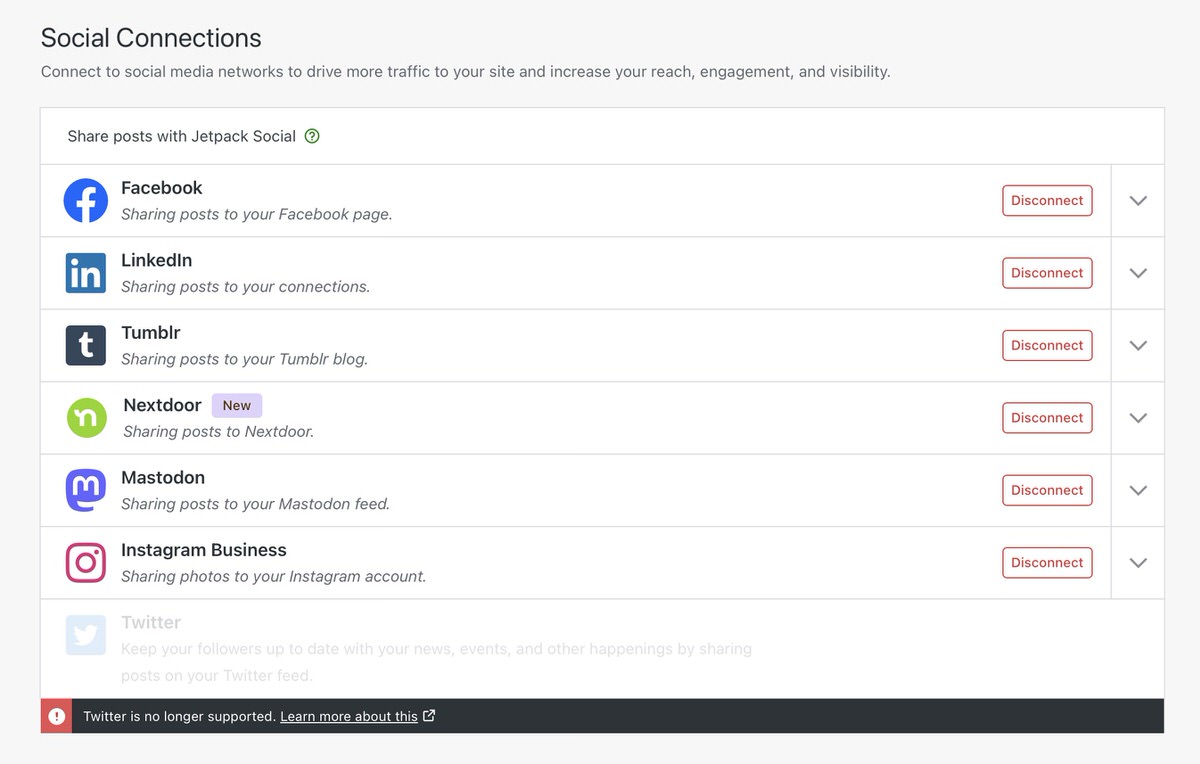

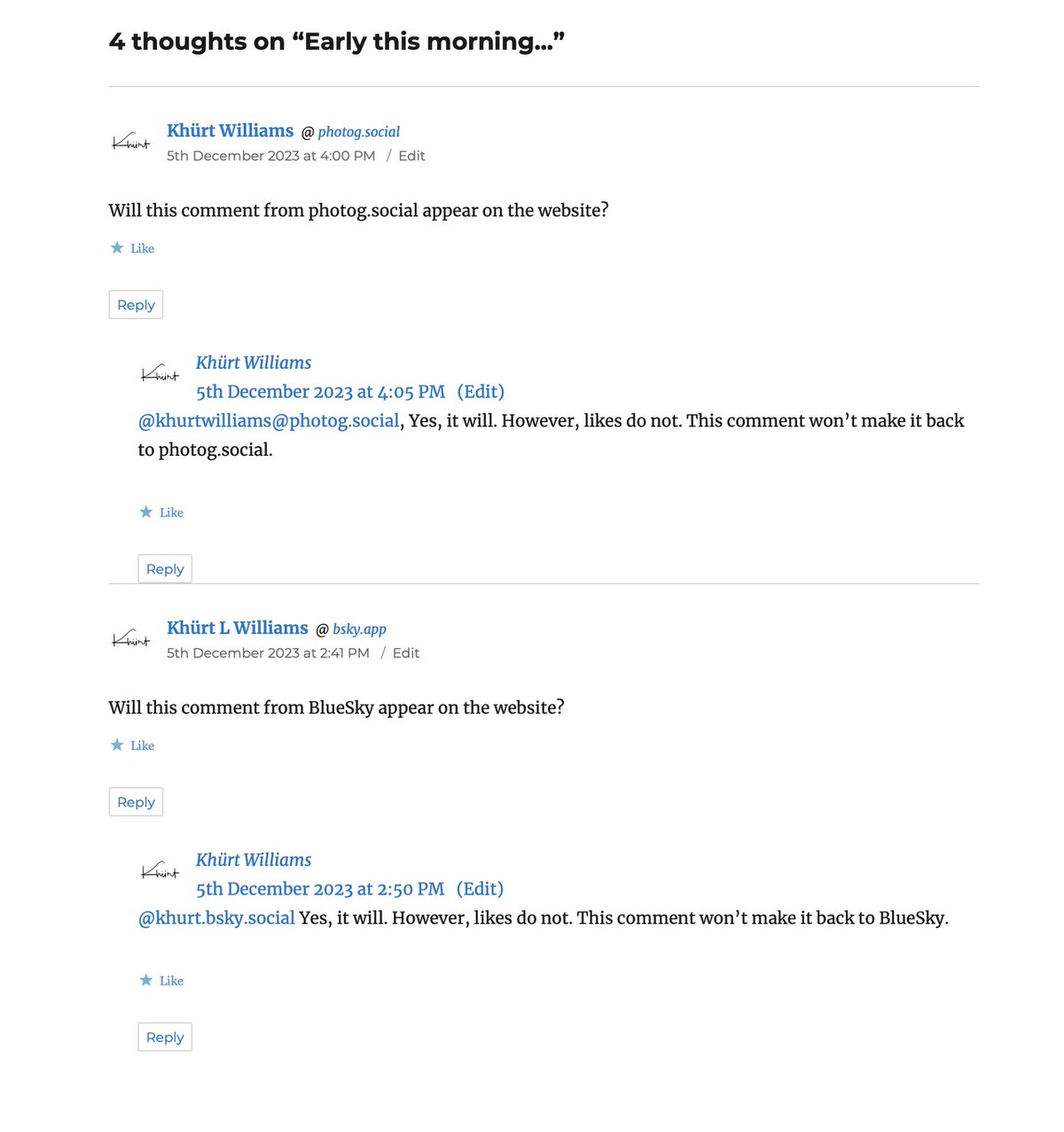

My posts are syndicated (POSSE) across various social platforms and managed through Automattic's JetPack Social and ActivityPub plugins. Comments on these platforms, however, only merge back into my blog with additional tools like Brid.gy, which only partially solves the problem.

The engagement on my blog primarily comes through native comments, WordPress Reader, micro.blog, and the photog.social Mastodon instance. Interaction from platforms like BlueSky is minimal, with limitations in displaying 'likes' and backfeeding comments.

Preparing a blog post to handle comments "backfed" by "Brid.gy" from platforms like BlueSky and photog.social requires manual effort, such as adding specific syndication links post-publication. Interactions via micro.blog requires manual HTML formatting to include microformat2 classes.

Reflecting on insights from the Incoming criticism section on the IndieWeb challenges page, I can see that I am not alone in how I feel about this.

As Kev Quirk notes in "Will the IndieWeb Ever Become Mainstream?":

Unless something drastic changes with the fundamental makeup of the IndieWeb, I don't think it will ever gain anything close to mass adoption. Maybe if WordPress picked it up and rolled into the system by default, then it would have a chance; but short of that, I don't see it happening.

I felt excitement when Kev speculated about the potential impact of Automattic integrating IndieWeb features into WordPress.

I am wondering if continued use of the Syndication Links plugin is worthwhile. The Syndication Links plugin is supposed to automatically add syndication links on each blog post, so I don't need to do it manually. However, the Syndication Links plugin is not integrated with any JetPacks social sharing services - Instagram, Facebook, NextDoor, Mastodon, Tumblr, and LinkedIn. So when JetPack shares my content to Instagram, Facebook, NextDoor, Mastodon, Tumblr, or LinkedIn, the Syndication Links plugin is unaware and does not set a u-syndication link. I had been visiting each social platform, copying the shared link, opening the original blog post for editing, and manually setting the link. It's tedious.

Given that Brid.gy was forced to abandon Instagram, X, and Facebook, and does not support NextDoor, Tumblr, and LinkedIn, the Syndication Links plugin is not useful for helping Brid.gy "backfeed" comments and reactions from those platforms. The time and effort involved in backfeeding comments from social platforms have led me to question the practicality of continuing the use of most of the IndieWeb plugins.

While IndieWeb tools aim to improve data portability, the varying standards and protocols often result in interoperability issues, making seamless data exchange between different systems challenging. As of today, I've turned off all IndieWeb plugins except Webmention and Syndication Links.