This week's challenge was challenging for me. I was looking up the definition of nostalgia.

a sentimental longing or wistful affection for the past, typically for a period or place with happy personal associations.

I was born and raised in the former British West Indies. The culture, food, buildings and beaches are not duplicated in anything that can be found in New Jersey. Or anywhere else on the East Coast. Or the United States. I spent my youth living in St. Vincent, Bequia, St. Lucia, Barbados, and Antigua.

The family home and the turquoise waters of the Caribbean Sea are thousands of miles away. I spent my early years living upstairs in the old Barclays Bank in Princeton Margaret beach in Bequia. The entrance to the building was about 200 meters from the beach. This is where I spent a lot of time with my brothers and friends. We played beach cricket with tennis balls and bats improvised from the dead branches of coconut trees. Sometimes we played intense games of marbles "for keeps". I don't remember the rules of marble games, but I know the games were hotly contested. Sometimes we just ran up and down the beach as fast as possible. I was always the fastest.

Sometimes my Mom would take us to visit our grandparents at their home on Monkey Hill. I loved helping my grandmother gather eggs from the chickens. Less enjoyable was moving the goats from one pasture to another. Goats can be difficult. If I was lucky, Mama1 would take me with her to pick sapodilla and sugar apples and we would climb all the way to the very top of Monkey Hill. There was always a good breeze, and I could see everything down to the coast below.

Those were good times.

I have no access to any of that, and in the thirty-two years I have lived in the United States, I can’t think of anything I have experienced in the USA that evokes those memories. The Jersey Shore beach water is brown. The ocean air does not smell the same. The food is American. It doesn’t feel the same.

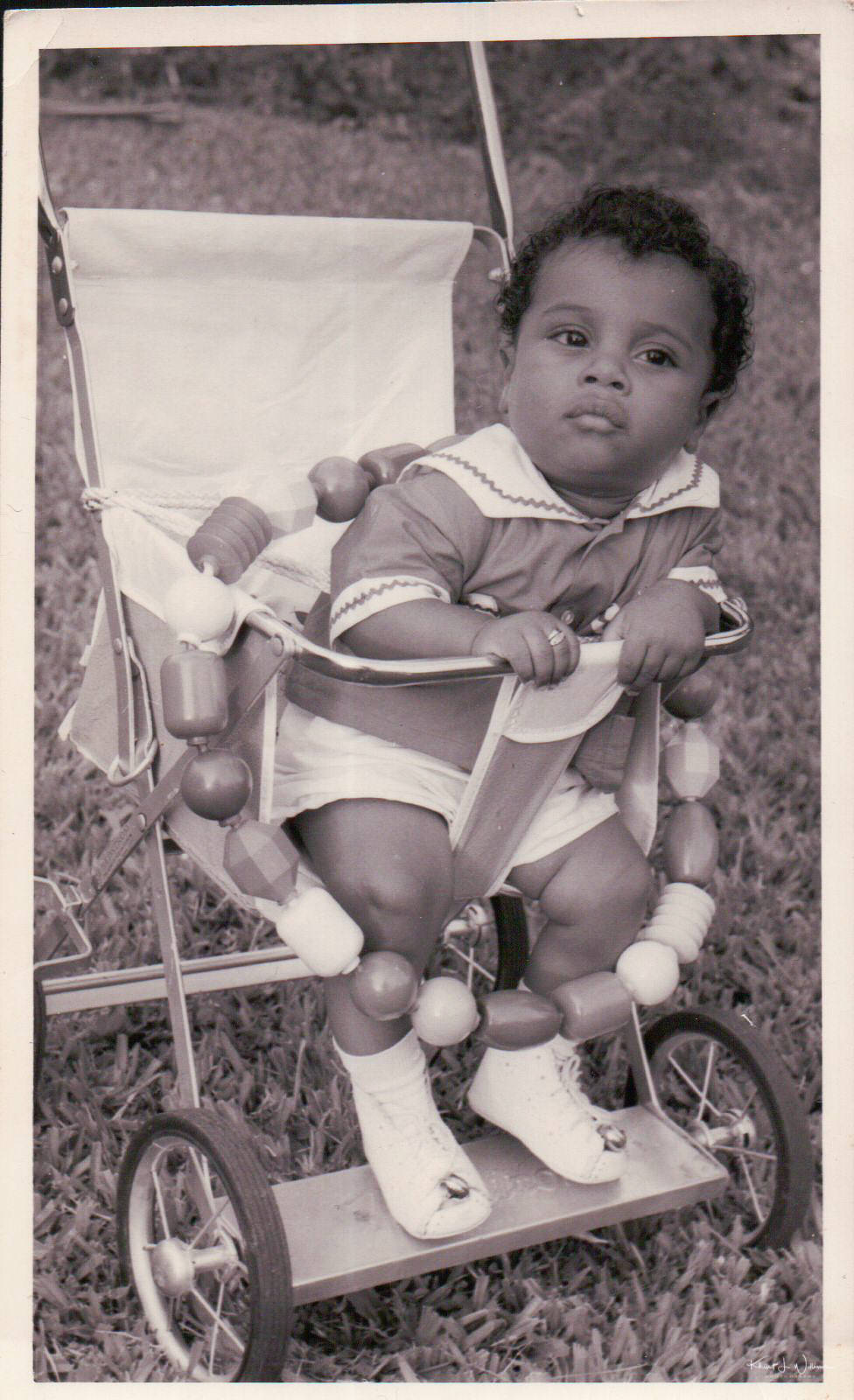

I don't have old photos to share. My parents either didn't own a camera at that time, or my mom has them in some precious album of her own. My mom lives in Florida, but right now is on holiday in St. Vincent.

I drove over to a shop in Hopewell, Twine, looking for inspiration. Twine sells various items; wooden boxes, old painted stools, flashcards, pencils, scrabble tiles, labels, books, etc. My daughter came with me. The only thing that seemed nostalgically familiar was the stack of marbles. I bought a handful.

Next door was an antique store, Tomato Factory. I saw a few things — vintage oil lanterns — that reminded me of my early life in the British West Indies, but ultimately there was nothing that I could take home. Photography in the store was not allowed.

This marbles photo does not include boys in khaki pants, beach sand or sunsets.

I was saddened while I was writing this. All this thinking about my past had made me acutely nostalgic. I realise how much I have lost.

The Tuesday Photo Challenge is a weekly theme-based challenge for photographers to share both new and old photography. This week's theme is nostalgia.

- All the grandchildren called her “mama”. ?